Context

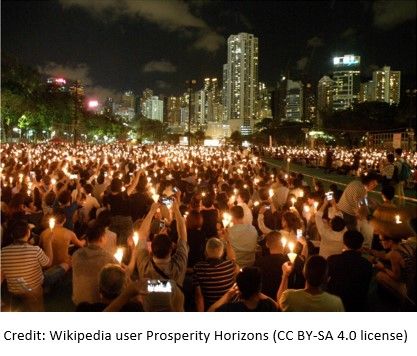

Since 1989, June Fourth vigil has become a day of peaceful demonstrations in Hong Kong with thousands of Hong Kongers gathered in Victoria Park, lighting candles to commemorate the victims every year. For years, Hong Kong has been the only city on Chinese controlled soil to mark June Fourth anniversary. Hong Kong had also been holding one of the world’s largest June Fourth vigils yearly.

However, since COVID-19 hit Hong Kong in 2020, the Hong Kong government invoked social distancing measures to ban the annual candlelight vigil and weaponized a number of domestic laws, including National Security Law, Public Order Ordinance, sedition charge under Crime Ordinance, to combat June Fourth commemorations both online and offline. Even though all COVID-19 restrictions in Hong Kong were lifted earlier in 2023, the vigil is still on hold for the fourth year with police arresting and detaining people for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of peaceful assembly or freedom of expression on that day.

Timeline (2019-2023) on June Fourth in Hong Kong

2019

- In the summer of 2019, the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement marked by a series of large scale demonstrations broke out with millions of Hong Kong citizens taking to the street.

- On June 4, the annual candlelight vigil at Victoria Park was attended by an estimated 180,000 people peacefully, one of the largest crowds in years.

2020

- In spring 2020, COVID-19 started to hit Hong Kong and the government introduced social distancing measures, including restricting all public gathering and assembly.

- The Anti-ELAB movement was forced to halt in face of all the restrictions and entered a period of “enforced abeyance”.

- Hong Kong police banned the annual June Fourth vigil for the first time in 30 years, citing public gathering restrictions.

- The organizers, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China (Hong Kong Alliance), still planned to go to Victoria Park and set up booths around the city to observe the event.

- Hong Kong Alliance also called for online commemoration.

- On June 4, thousands gathered in Victoria Park to attend the annual candlelight vigil to mark the 31st anniversary in defiance of a police ban.

- 24 pro-democracy figures were arrested in connection with the banned June 4 candlelight vigil.

- On May 6, 2021, 4 were sentenced to 4 to 10 months in jail.

- On September 15, 2021, 12 were sentenced to 6 to 10 months in jail.

- On December 13, 2021, 8 remaining were sentenced to 4 months 2 weeks to 14 months in jail.

- On June 30, the National Security Law was enacted. It criminalizes secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign organizations.

2021

- Hong Kong police banned the annual June Fourth vigil for the second time, citing coronavirus restrictions again.

- On June 1, officers from the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department investigate June Fourth Museum operated by the Hong Kong Alliance alleging the museum lacked an operating licence under the Places of Public Entertainment Ordinance.

- On July 27, it was fined HK$8,000

- Hong Kong Alliance decided not to take the vigil online this year.

- On June 2, Hong Kong Alliance shut down the June Fourth Museum.

- On June 4, Chow Hang-tung, barrister and former vice-chairwoman of Hong Kong Alliance, as well as a 20-year-old man were arrested under the Public Order Ordinance for “publicizing unauthorized assembly” online.

- On January 4, 2022, Chow was sentenced to 10 months in jail for inciting to participate (an additional sentence of one year in jail was for participating in the same event in 2020).

- On June 4, more than 200 police sealed off Victoria Park in the afternoon to prevent people from gathering for the banned vigil. In the nearby area, hundreds of black-clad residents were on the streets holding their lit mobile phones or candles.

- At least six people aged between 20 and 75 were arrested over June Fourth-related activities and another 12 people were fined for breaching social distancing rules.

- On August 4, after the forced closure of the physical June Fourth museum in Hong Kong, the virtual “8964 Museum (8964museum.com),” crowdfunded by the Hong Kong Alliance went online.

- On August 24, national security police sent letters to 12 members of the group requiring them to provide information for investigation, under paragraph 5 of Article 43 of the National Security Law. In the letter, the group was accused of being a “foreign agent”.

- On September 8-9, five members of the standing committee of the Hong Kong Alliance were arrested for their refusal to provide information demanded by the national security police.

- On September 10, three key members were charged with inciting subversion under the National Security Law.

- On September 26, Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements disbanded.

- On September 29, national security police froze all assets of Hong Kong Alliance.

- On September 30, access to “8964 Museum (8964museum.com)” website was blocked in Hong Kong.

- In late December, June Fourth monuments in different universities were removed.

2022

- Hong Kong police banned the annual June Fourth vigil for the third time, without any application from any organizer. Football pitches at Victoria Park were also fully booked on June 4, with officials saying the premises would be available for sports on that day but not for “other purposes”.

- At least 100 police officers patrolled Victoria Park on June 3 with parts of the park cordoned off and a man arrested based on his comments online and other online activity.

2023

- The vigil was on hold for the fourth year, with government officials saying Victoria Park, has been closed for renovations until the end of June, while a pro-Beijing group was approved to host a carnival sales event in the remaining area.

- All COVID-19 restrictions were lifted earlier this year.

- Other demonstrations resumed and approved earlier this year with the police setting out new requirement (wearing numbered badge) for holding assembly, citing security reasons.

- 5,000 police officers were deployed during the weekend of June 3 and 4 to patrol streets, set up roadblocks, and conduct stop-and-search checks around Victoria Park to guard against unauthorized gatherings.

- 23 people aged between 20 and 74 were detained for “breaching public peace,” and one 53-year-old woman was arrested for obstructing police officers over June Fourth-related activities.

Remembering June Fourth is not a crime

Following the arrests and detentions of dozens of people over the June Fourth commemoration in Hong Kong in 2023, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights made the following statement on Twitter: “We are alarmed by reports of detentions in #HKSAR linked to June 4 anniversary. We urge the release of anyone detained for exercising freedom of expression & peaceful assembly. We call on authorities to fully abide by obligations under Int’l Covenant on Civil & Political Rights.”

According to General Comment No. 37 (2020) by the Human Rights Committee, the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and the right to freedom of expression are inextricably linked. The Committee explained that the full protection of the right of peaceful assembly is possible only when other, often overlapping, rights are also protected, notably freedom of expression, freedom of association and political participation. Therefore, protection of the right of peaceful assembly is often also dependent on the realization of a broader range of civil and political rights, and economic, social and cultural rights. In fact, the right to freedom of peaceful assembly is of particular importance to marginalized individuals and groups. The committee noted that the failure to respect and ensure the right of peaceful assembly is typically a marker of repression.

In addition, General Comment No. 37 emphasizes online assembly, in a world where we cannot talk about assemblies and peaceful protests without thinking about online spaces which people use nowadays to mobilize and express themselves freely. The importance of online assembly was heightened during important during COVID-19, where this was the only space where people could organize, express their political views, and to connect with their leaders. In the case of the June Fourth commemoration in Hong Kong in recent years, it became even more significant that Hong Kongers could assemble online in the face of COVID-19, no matter that meant posting messages in solidarity online, attending online vigils, or even visiting the digital June Fourth museum.

The State also has obligations when it comes to protecting online assemblies. The General Comment notes that States parties must not, for example, block or hinder Internet connectivity in relation to peaceful assemblies. The same applies to geotargeted or technology-specific interference with connectivity or access to content. States should ensure that the activities of Internet service providers and intermediaries do not unduly restrict assemblies or the privacy of assembly participants. Any restrictions on the operation of information dissemination systems must conform with the tests for restrictions on freedom of expression. While the Hong Kong authorities have not resorted to extreme measures to prevent online assemblies, the criminalization of online activity on June Fourth has only discouraged Hong Kongers from expressing themselves freely, with many of them resorting to self-censorship to avoid criminal sanctions (as described in earlier paragraphs).

The various restrictions on June Fourth activities and assemblies imposed by the authorities in Hong Kong do not comply with Article 21 of the ICCPR. The General Comment explains that while the right of peaceful assembly may in certain cases be limited, the onus is on the authorities to justify any restrictions. Authorities must be able to show that any restrictions meet the requirement of legality, and are also both necessary for and proportionate to at least one of the permissible grounds for restrictions enumerated in article 21, as discussed below. Where this onus is not met, article 21 is violated. The imposition of any restrictions should be guided by the objective of facilitating the right, rather than seeking unnecessary and disproportionate limitations on it. Hong Kong authorities have simply resorted to using COVID-19 gathering restrictions to prevent any activities from happening, with no justification given. This is not sufficient justification.

Further, General Comment No. 37 notes that blanket restrictions on peaceful assemblies, such as those employed by the Hong Kong authorities, are presumptively disproportionate. The prohibition of a specific assembly can be considered only as a measure of last resort. Where the imposition of restrictions on an assembly is deemed necessary, the authorities should first seek to apply the least intrusive measures. States should also consider allowing an assembly to take place and deciding afterwards whether measures should be taken regarding possible transgressions during the event, rather than imposing prior restraints in an attempt to eliminate all risks. In this light, with the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions in early 2023, it is unfathomable that June Fourth vigil and activities continue to be routinely banned with absolutely no justification or alternatives given.

The Hong Kong authorities must stop restricting the online and offline exercise of rights to freedom of expression and freedom of peaceful assembly in Hong Kong (Read more on FAQ ON FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY (HONG KONG)). Most importantly, remembering June Fourth is not a crime.

Related Resources

“FAQ ON FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY (HONG KONG),” Human Rights in China, updated August, 2023.

Keith Richburg, King-wa Fu, Louisa Lim, Edmund Cheng, Samson Yuen and wen yau, “1989-2019: Perspectives on June 4th from Hong Kong,” China Perspectives, January 1, 2019.

“Hong Kong Timeline 2019-2022: Anti-Extradition Protests & National Security Law,” Human Rights in China, updated May 16, 2022.

“Too Soon to Concede the Future: The Implementation of The National Security Law for Hong Kong—An HRIC White Paper,” Human Rights in China, October 16, 2020.

“June 4 vigil in Hong Kong,” South China Morning Post, updated June 24, 2023.